CEFS: Finally Solving CE's Mount(ing) Problems

Written with LLM assistance.

Details at end.

Today we finished migrating Compiler Explorer to CEFS — the Compiler Explorer File System1. After three years of attempts, we finally have a working solution for mounting our thousands of SquashFS compiler images on demand instead of all at boot time.

If you want to know why on earth we’d be mounting thousands of SquashFS images at bootup, have a look at my post on how Compiler Explorer works – it’s a long tale of trying to squeeze performance out of NFS2.

The problem was straightforward but annoying. We have 2,182 SquashFS images containing compilers, tools and libraries; and until today we mounted every single one when our instances started up. This took 30-50s and kept metadata for thousands of filesystems in kernel memory. The obvious solution – mount on demand – turned out to be surprisingly tricky when you have compilers at different directory depths and need the underlying NFS filesystem to remain visible for compilers without SquashFS images. Moving things around was a no-go, I couldn’t find a way to safely rename/move all our compilers without inevitably breaking something.

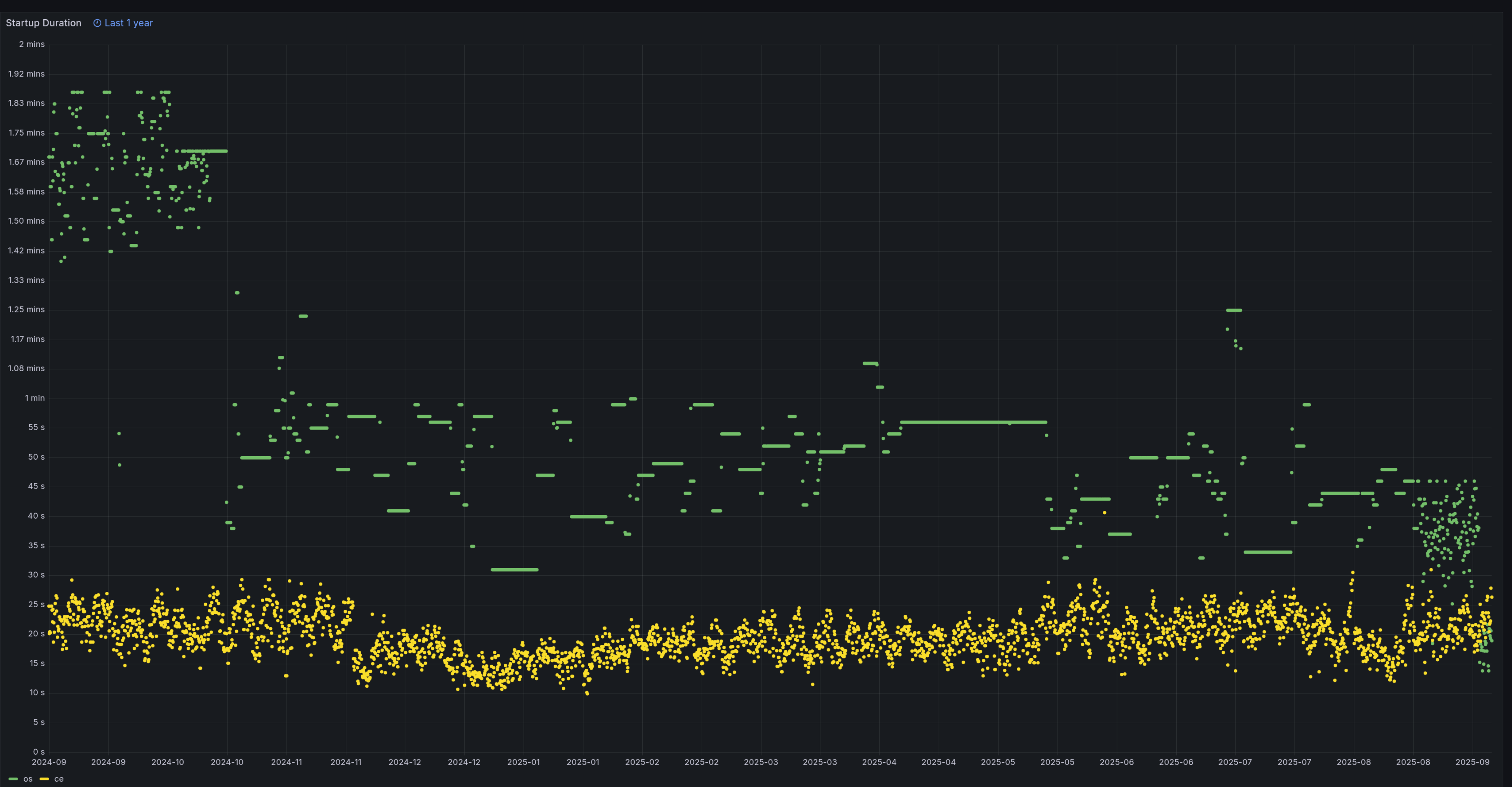

Startup times over the last year. CEFS went live just now — OS setup time (pre-CE) dropped from 50s to 20s, while CE startup remains unaffected at around 20s.

I first attempted this back in September 20223. That initial proof-of-concept tried to replace /opt/compiler-explorer entirely with some “supermagic squashfs things” as I called it in the pull request. It didn’t quite work out. Over the next couple of years, we tried various approaches: a Rust-based FUSE filesystem4, different AutoFS configurations, overlayfs experiments. Each attempt hit different snags; sometimes technical, sometimes operational.

The breakthrough came when we realised we could use content-addressable storage with symbolic links. Each compiler gets built into its own SquashFS image. We hash the contents with SHA256 and store it on NFS under that hash name. Instead of /efs/squash-images/gcc-13.1.sqfs, we now have something like /efs/cefs-images/38/389c688f98ba10ac7e68ed40_gcc_13_1.sqfs.5

We replace the compiler’s actual directory with a symbolic link pointing to /cefs/<ha>/<hash> (where <ha> is the first two characters of the hash). When something tries to access that path, AutoFS automatically mounts the equivalent SquashFS image at that location (/efs/cefs-images/<ha>/<hash>.sqfs). The mount happens transparently — the first access triggers it, and after that it’s almost as fast as having the files directly on disk. No changes needed in the application code.

Mounting individual images on demand was good, but we can improve from there. Instead of thousands of individual SquashFS images, we now consolidate compilers into larger bundles of around 20GB each.

The consolidation tooling automatically scans all available images and packs them together without any particular strategy — we just lump things together as we find them. Typically we get a half dozen Clangs per bundle, tens of GCCs, or hundreds of smaller tools in a single image. This brings our total from 2,187 individual images down to just 121.

Here’s an example of what the drive looks like:

$ ls -l /opt/compiler-explorer/ | grep gcc | head -5

... 67 Sep 10 22:03 gcc-1.27 -> /cefs/22/22e6cdc013c8541ce3d1548e_consolidated/compilers_c_gcc_1.27

... 75 Sep 10 21:49 gcc-10.1.0 -> /cefs/73/73574545c1246435e304eea2_consolidated/compilers_c++_x86_gcc_10.1.0

... 75 Sep 10 21:49 gcc-10.2.0 -> /cefs/73/73574545c1246435e304eea2_consolidated/compilers_c++_x86_gcc_10.2.0

... 75 Sep 10 21:49 gcc-10.3.0 -> /cefs/73/73574545c1246435e304eea2_consolidated/compilers_c++_x86_gcc_10.3.0

... Sep 10 21:49 gcc-10.4.0 -> /cefs/73/73574545c1246435e304eea2_consolidated/compilers_c++_x86_gcc_10.4.0

$

The gcc 1.276 and the gcc 10 family have been consolidated into different images. Looking inside the packed image root shows what else has been packed in the same image:

$ ls /cefs/73/73574545c1246435e304eea2_consolidated

compilers_c++_nvhpc-sdk_x86_64_25_5 compilers_c++_x86_gcc_10.2.0 compilers_c++_x86_gcc_12.1.0

compilers_c++_nvhpc-sdk_x86_64_25_7 compilers_c++_x86_gcc_10.3.0 compilers_c++_x86_gcc_12.2.0

compilers_c++_plugins_clad_1.10-clang-20.1.0 compilers_c++_x86_gcc_10.4.0 compilers_c++_x86_gcc_12.3.0

compilers_c++_plugins_clad_1.8-clang-18.1.0 compilers_c++_x86_gcc_10.5.0 compilers_c++_x86_gcc_12.4.0

compilers_c++_plugins_clad_1.9-clang-19.1.0 compilers_c++_x86_gcc_11.1.0 compilers_c++_x86_gcc_12.5.0

compilers_c++_plugins_clad_2.0-clang-20.1.0 compilers_c++_x86_gcc_11.2.0 compilers_c++_x86_gcc_13.1.0

compilers_c++_tinycc_0.9.27 compilers_c++_x86_gcc_11.3.0 compilers_c++_x86_gcc_13.2.0

compilers_c++_x86_gcc_10.1.0 compilers_c++_x86_gcc_11.4.0

Now when someone accesses any compiler in an image, the entire image becomes available with just one mount operation. With only 121 total images, there’s a decent chance something else has it already, and so often there’s no delay on the mount. Monitoring shows we have around 40-50 mounts active at any time.

One challenge was handling compiler updates. With consolidated images, replacing a single bad compiler build would normally require repacking everything, which takes considerable time. Our solution maintains operational flexibility by layering updates. When we need to replace a compiler that’s already in a consolidated image, we create a new single-compiler image containing just the replacement, and update the symlink to point there instead.

This means the old compiler remains in the consolidated image as “dead data” that’s never accessed, but we can deploy fixes immediately without waiting for repacking. A garbage collection process later identifies fully unused consolidated images and can repack underutilised ones when convenient7.

We have built some pretty cool tooling around all this:

$ ce_install cefs status --show-usage --verbose

CEFS Configuration:

Enabled: True

Mount Point: /cefs

Image Directory: /efs/cefs-images

Local Temp Directory: /tmp/ce-cefs-temp

Squashfs Configuration:

Traditional Enabled: False

Compression: zstd

Compression Level: 7

CEFS Image Usage Statistics:

Scanning images and checking references...

Image Statistics:

Total images: 121

Individual images: 84

Consolidated images: 37

- Fully used (100%): 34

- Partially used: 3

* 75-99% used: 3 images

- Unused (0%): 0

Space Analysis:

Total CEFS space: 702.06 GiB

Wasted in partial images: ~396.69 MiB (estimated)

The AutoFS configuration is deceptively simple9. We use a two-level hierarchy to handle the scale — the first two characters of the hash become a subdirectory, so /cefs/38/389c688f98ba10ac7e68ed40_consolidated mounts /efs/cefs-images/38/389c688f98ba10ac7e68ed40_consolidated.sqfs. This keeps any single directory from having thousands of entries, which can cause performance issues with some filesystems.

Most of the current implementation was built with Claude Code’s help, with careful oversight and testing. The migration completed today. We’ve successfully moved all our previous hard-coded SquashFS mounts to this new system of symlinks and AutoFS.

We have around 700G of SquashFS images, about the same as our previous setup:

$ du -sh /efs/cefs-images/ # new system

703G /efs/cefs-images/

$ du -sh /efs/squash-images/ # old system

688G /efs/squash-images/

Once I’m brave enough I’ll delete the squash-images. It’s been a slow and careful process, and at each stage we kept .bak files for everything we changed for quick rollback. I just removed most of them after “proving” to myself I hadn’t broken anything.

The system now provides faster boot times, lower memory usage, and the operational flexibility to update individual compilers without complex repacking operations8. We’re considering extending this approach to other large static assets like library headers and documentation.

There’s also potential for smarter consolidation strategies, though the current approach of “just pack whatever needs packing” is likely good enough. Down the road we could add statistics and monitoring of the mounts, and see what actually gets used, but frankly I’m just happy nothing appears to have broken. Especially as it’s CppCon next week and really I should be working on slides!

Overall it’s not too shabby for an idea that’s been kicking around since 2022. Sometimes the third attempt really is the charm.

Disclaimer

This article was written with LLM assistance: I dictated my ideas and large sections to Claude while I was walking the dog, and got it to draft a blog post based on that. Once I got home from the walk, I used Claude Code to help research the GitHub history of CEFS, gather metrics from our infrastructure, and edit the draft. The LLM also helped with proofreading and ensuring I included all the technical details. The opinions, experiences, and puns are all mine though.

-

Naming is hard, and I didn’t look far but I know there’s a bunch of other CEFSes out there. Oops. ↩

-

Sometimes I think all software engineering boils down to patching over the problems you created for yourself the time before. I find myself singing “There was an old woman who swallowed a fly…” under my breath sometimes as I force a horse into my program to catch the cow… ↩

-

PR #798 - “New approach to squashfs images” - my first attempt at replacing

/opt/compiler-explorerwith “supermagic squashfs things”. It didn’t work out, but planted the seed. ↩ -

A private repository contains the archived Rust FUSE filesystem implementation. It was a somewhat decent attempt but the complexity of FUSE programming and the operational requirements made it tricky. And I didn’t fancy debugging it when it inevitably went wrong. ↩

-

Our original design just had the hash in the name, and had all sorts of clever reproducibility stuff that meant we actually used the content addressability. But, that made other things break, so we never used it, and then it became useful to have something human-readable in the name too. So, it’s not really CAS any more. ↩

-

That’s the oldest GCC we support, from 1988. ↩

-

Currently the garbage collection is manual — I want to babysit it each time. Eventually when we’re confident, we’ll automate it to run weekly or something like that. ↩

-

This was actually a problem with the old way; a squashed image couldn’t be replaced without restarting all our CE instances, which was painful. ↩

-

Setting up the multi-level AutoFS is a bit painful — if you’re curious about the implementation details, see the setup script that configures it. ↩